Wednesday, 8 May 2013

Humpty Dumpty and the TAUS quality concept

Wednesday, 25 April 2012

Computer language mystery solved by humans

Friday, 2 March 2012

Would I advise my grandchildren to translate?

BEG, SCAVENGE and STEAL

BEG, SCAVENGE and STEALFriday, 11 November 2011

DVX2 screenshot gallery

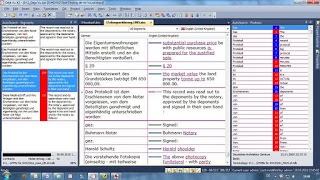

In this "tramline" layout, the working area is in the middle of the screen and the reference material is arranged to the right and left. It provides more context (i.e. the text before and after the active sentence). The shorter lines could be a disadvantage for longer sentences, and especially on smaller screens. The above screenshot is taken from my 22" monitor. On my 10" netbook, this layout is rather more cramped, although it would be just about workable:

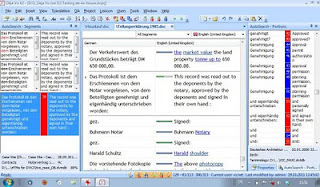

In this "tramline" layout, the working area is in the middle of the screen and the reference material is arranged to the right and left. It provides more context (i.e. the text before and after the active sentence). The shorter lines could be a disadvantage for longer sentences, and especially on smaller screens. The above screenshot is taken from my 22" monitor. On my 10" netbook, this layout is rather more cramped, although it would be just about workable: One way to make the lines longer in the working area is to work in a separate text area at the bottom of the screen and to split this text area vertically (Tools>Options>Environment). The active sentence is highlighted in the grid, but the working area is now at the bottom, i.e.:

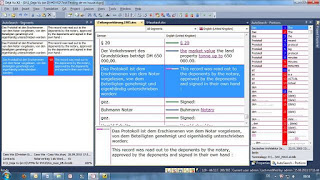

One way to make the lines longer in the working area is to work in a separate text area at the bottom of the screen and to split this text area vertically (Tools>Options>Environment). The active sentence is highlighted in the grid, but the working area is now at the bottom, i.e.: I often get jobs with very long sentences, and sometimes the reference pane on the left is empty for most segments. In such jobs, I can simply hide this column, which gives me longer text lines even without using the separate text area:

I often get jobs with very long sentences, and sometimes the reference pane on the left is empty for most segments. In such jobs, I can simply hide this column, which gives me longer text lines even without using the separate text area: The top of the DVX2 window shows the name and path of the current project. For example, the project I used for these screenshots is on drive D at the location shown.

The top of the DVX2 window shows the name and path of the current project. For example, the project I used for these screenshots is on drive D at the location shown.

Wednesday, 19 October 2011

Deep mining with Déjà Vu X2

Over the last 12 years I have seen three generations of the program. The first version was known by the abbreviation "DV3". The next generation, DVX, was released in May 2003. The latest version is DVX2, which was released in May 2011.

Each new version has new features. A list of new features in DVX2 can be found here. One new feature which has puzzled many people is "DeepMiner". The theory is that it uses both the TM and the terminology databases to retrieve even more material. But how does it work in practice? There is a training video which uses an extremely simple example to show cross-analysis between the sentences "I have a brown dog" and "I have a black dog" when translating them into French.

So far so good. In practice, however, my sentences are never as simple as this example, and the size of my databases means that DeepMiner has to work much harder. As a result, using DeepMiner on a largish project with big databases can be very slow. And in my experience, DeepMiner is sometimes not helpful because it tries to be too clever and reconstruct the solution from similar sentences in the TM, and in the process it may overlook what I have in my termbase and lexicon. Thankfully, it is easy to switch the DeepMiner function on or off.

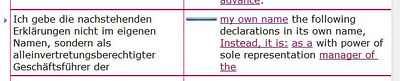

So how helpful is this new function? To illustrate this, let's look at one example sentence from a complicated German land purchase and partitioning contract in two alternative versions: with and without DeepMiner:

My translation:

I make the following declarations not in my own name, but as a manager with power of sole representation of ...

Looking at the first half of the sentence, where do the phrases "my own name" and "the following declarations" come from in the example with DeepMiner? They are not in the terminology hits for this segment, and there is no whole sentence match. But the TM has many matches containing "die nachstehenden Erklärungen" and the translation "the following declarations" (although "nachstehend" on its own is only in the TB as "hereinafter"). The first three words "my own name" seem strange at first sight. Somehow, DeepMiner seems to have found a correlation between the words "ich ... im eigenen Namen" and the English "my own name", in spite of the fact that the TB entries which use "im eigenen Namen" only offer the English "its own name" and "his own name".

At least in this example, DeepMiner offers solutions which go beyond the conventional assembly and pretranslation routines in the previous version of DVX. In my experience, it is still a matter of trial and error - sometimes it finds surprisingly good suggestions, but sometimes it is not really helpful. One possible workflow to get the best of both worlds is to "Pretranslate" the whole file with DeepMiner activated and then, if the solution is not helpful, to "Assemble" the individual sentence without DeepMiner. To do this, the settings for Pretranslate are:

And the settings for Assemble (under Tools>Options>General) are:

I am still experimenting to find out how DeepMiner can be used to best advantage, so perhaps I will be able to add more insights at a later date. Before too long (hopefully) I will comment on some of the other features of DVX2 such as AutoWrite, the information design options in the variable grid layout etc.